Going Down the Xenotransplant Rabbit Hole (Part 2)

Last week brought some optimistic news—Towana Looney, the 53-year-old

woman from Alabama who received a kidney transplant from a genetically

engineered pig in New York on November

25th 2024 is doing well—and so is the transplant.  Per news reports,

she is out of the hospital, has normal labs, feels great, and

will hopefully return home soon. Ms. Looney is now the longest

surviving recipient of a functional pig xenotransplant. This is

uncharted territory and each day is a new milestone.

Per news reports,

she is out of the hospital, has normal labs, feels great, and

will hopefully return home soon. Ms. Looney is now the longest

surviving recipient of a functional pig xenotransplant. This is

uncharted territory and each day is a new milestone.

Expanded Criteria?

So far, xenotransplant attempts have been made under the FDA Expanded Access pathway (also known as “compassionate use”) which allows experimental treatments to be trialed when circumstances are deemed exceptional or dire and there are no further conventional options to be offered. Prior to late last year, the patients selected for xenotransplantation were either (brain) dead or had a very short life expectancy—so short that there would be no measurable loss of lifespan if the treatment proved unsuccessful.

As I mentioned in my previous blog about the xenotransplant push forward, these criteria may be changing. They may even have changed already.

Learning from the Heart

The first living recipient of a porcine heart was David Bennett, a 57-year-old Maryland man who lived for 2 months after his xenotransplant. During weeks of hospitalization for heart failure he suffered several ventricular arrythmias followed by cardiac arrests and resuscitations.

His prognosis extremely grim, Mr. Bennett was placed on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and evaluated for allotransplantation. He was denied at four transplant programs after having been deemed “medically non-compliant” and thus, ineligible to receive a human heart. It was then that the experimental xenotransplant was offered. Mr. Bennett agreed. It was his only chance at survival, and he wanted to live.

Mr. Bennett’s surgery took place January 7, 2022. Unfortunately, complications prevented his recovery—kidney failure requiring dialysis, peritonitis, arrhythmias, cachexia, etc. Though Mr. Bennett was able to get out of bed on post-op day 48, he quickly declined afterwards, was back on life support by day 50, and terminally removed from it on day 60. His cause of death was interestingly heart failure, not rejection.

Upon autopsy, the pig heart had doubled in size. It was also unexpectedly found to be carrying porcine cytomegalovirus (pCMV)—which was transmitted to Mr. Bennett. How much the pCMV contributed to his heart failure is not known, but it is suspected to be the cause. In non-human primates, the presence of pCMV in xenotransplants was associated with shorter survival. A lot was learned from the David Bennett case.

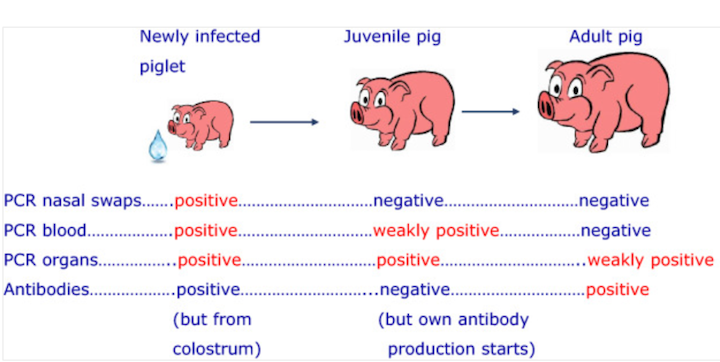

How Did the Donor Pig Contract pCMV?

As it turns out, pCMV is common in pigs and boars. The donor pig used was weaned early, raised in a biosecure facility, and had screened negative for the virus prior to the transplant. The virus may have been transmitted to the piglet through its mother’s milk prior to weaning and remained latent until it was transmitted. From the link above:

From Living Donor to Xenorecipient

One thing that makes the Towana Looney case so interesting for me is that, aside from her kidney failure, she seems to be relatively healthy. As part of the circumstances that make her case so extraordinary, she donated a kidney to her mother in 1999. The damage to her remaining kidney was the result of a hypertensive pregnancy complication years later. When Towana needed dialysis in 2016, she may have been aware that fewer than 1% of living kidney donors end up needing an organ themselves, but those who do are automatically given a higher priority status on deceased donor transplant lists.

Ms. Looney was placed on the waitlist for a kidney in 2017, but had a very low, “one in a million” chance of being called for a transplant due to having received blood transfusions and developing high sensitization to, per her surgeon, “nearly every tissue type in the population.” I do not know if, or to what extent, HLA desensitization was appropriate or trialed, but it is something I am curious about. Ms. Looney would have likely have received a human kidney years ago were it not for her sensitization.

To further complicate matters, after 8 years of dialysis, Ms. Looney began to run out of viable access sites, compromising her ability to get dialysis in the future.

Biotech Organ Supply Dreams

The pig kidney offered as a “Hail-Mary” pass for Ms. Looney had 10 edited genes to prevent rejection. Revivicor, the United Therapeutics company that supplied her kidney—and Mr. Bennett’s heart—has reportedly applied to the FDA to start human trials in 2025 for the “UKidney” as an Investigational New Drug (IND) and plans to build at least two facilities to support xenotransplant studies to the tune of 250+ organs per year.

The other biotech company working on xenotransplants, eGenesis, supplied the pig kidney transplanted in Boston early last year. They are also working to solve the organ shortage problem and get closer to human clinical trials.

One of the goals of xenotransplant in general is to eliminate barriers to human-to-human transplant by creating and harvesting organs from animals we have some genetic control over, which could improve access for more people who want one.

New Questions Mimic History

Ethical questions about xenotransplants are being raised. It makes sense that nephrology would be one of the first specialties to discuss bioethics in this context. Some of the questions are the same as they always have been:

Could a genetically modified pig kidney someday be purchased by a patient, even though a human organ cannot be?

Would a purchase be similar to buying pork at the grocery store—or buying an organ on the black market?

How will xenotransplantation cost affect equity and access?

Would pig organs bio-engineered to function in human beings without a need for immunosuppressive medications be “better” than human organs?

If so, will that eliminate the need for human donors one day?

I do not know the status is of these projects right now, how the ethical conversations will morph over time, or how other issues in medicine and politics will impact the trajectory of xenotransplants. In the last couple of years, this topic has catapulted into the mainstream and the prospect of another choice for patients seems very close.

Zoonotic Disease is Worrisome

We are currently facing outbreaks of zoonotic disease in a global society. The finding of pCMV in the human recipient of a pig heart is particularly concerning, especially considering the pig had undetectable viral levels. Many of the papers I’ve been reading wonder how further transmission of zoonotic diseases via xenotransplant can be prevented. Other countries are also hoping to find an alternative source for human organs, and the developing regulations may be very different depending on locations. This can impact all of mankind in significant ways we likely do not fully realize yet.

Listen to Experts Speak

Here is a 2022 BBC Inside Health podcast featuring Dr. Jayme Locke, one of the cutting-edge nephrologists who has performed pig xenotransplants on deceased recipients and then Towana Looney. It also features David Bennett’s surgeons. If this is a subject that interests you, it is fascinating to hear from the people actively working on this science.

I hope to continue this discussion when there are new developments to report.

Comments