The Nurse Angle: Train Dialyzors, Not Care Partners!

Last week, my friend Henning Sondergaard (or, as I prefer to say, Sondergaaaaaaard!) published a blog about his experience as a solo home dialysis patient and thoughts on the concept of “learned helplessness” in chronic (specifically kidney) disease. I suggest you check out that blog, Train Dialyzors, Not Care Partners! as well as his predecessor post, Home Dialysis—An Antidote To Learned Helplessness, which Henning wrote in 2018.

You might ask yourself why, as a patient, my buddy Henning keeps feeling emboldened to write about this subject. Allow me to shine a little more light over there onto the delightful Dutchman (he likes it) because it’s myopic and easy to summarize his existence with a list of medical “stuff” rather than have any insight into who he is as a human, or why his perspective on this issue is…extra valid.

Henning mentions his credentials pretty casually (because he’s not egotistical), but I’d like to take this opportunity to emphasize the heck out of the fact that he is a psychologist. Not only is he thoroughly geeked out by the human condition, he took the steps necessary to become an expert on it.

Also, Henning has one leg and a couple of kidneys, none of which work—his “steps” are extra impressive because he actively had to fight back against feeling helpless to achieve what he has—and Henning has done some really wildly awesome things I can’t even talk about in here because of professionalism.

So, why does Henning write about care partners, and why does it matter?

Let’s Talk About Facebook

Issues involving deteriorating relationship dynamics between patients and their care partners is one of the most frequent topics of conversation (and controversy!) that comes up in the Home Dialysis Central Facebook Group. What we often hear about are situations where one person (usually not the patient) has been trained (by professionals!) to take on the brunt of the treatment tasks for absolutely no reason.

This partner is subsequently exhausted and under the impression that either this is “normal” or that the patient is incapable of doing more of the treatment by virtue of the illness. Both of these beliefs are untrue. Worse, the support person is often concomitantly saddled with all or most of the non-dialysis tasks too—the cooking, housekeeping, and executive life duties. Worse still, often this person is also trying to keep a job, financially support the household, take care of children, aging parents, pets, and crisis-manage. This scenario is a recipe for personal disaster and home dialysis failure.

In these situations, on one hand you have a patient who has been trained to believe it is normal to rely solely on another person (most often a spouse, but certainly not exclusively) for life support, while taking a passive role in their own care. On the other, you have a partner who is emotionally broken, falling apart at the responsibilities they’re trying to juggle, and adding “feeling guilty for being burned out because it’s a life-or-death thing” as a cherry on top.

Broken down like this, training care partners to help capable patients creates an obvious problem. Carers feel stuck and paralyzed with dependency within their relationships. They feel nothing will change, and since they can’t leave, they must endure. Truly a bad combination.

What ends up happening (Henning relates this to Stockholm Syndrome) is that both parties end up feeling trapped and held hostage unwillingly to the situation. This is unhealthy and nonconsensual. It’s psychologically distressing to everyone involved and raises all of my red flags.

There is a lot of room for meaningful change in our community to avoid setting patients and their partners up for the kind of relationship stress this adds to a medical situation that is absolutely stressful enough on its own. People need their support systems to get through hard times; burning out the support system is detrimental, and needs to stop.

Learned Helplessness

By virtue of Henning’s credentials, I can absolutely quote him as my source for a definition of “learned helplessness” and I will. Learned helplessness is, “the mental state that occurs when a [person] is forced into a situation that is painful or unpleasant” and remains in that state for a prolonged amount of time. Eventually, affected individuals are so exhausted that they genuinely stop believing they are capable of having any control over the situation, and thus they “stop fighting because they know there is no escape.” Later on, when they find themselves in another circumstance that is painful or unpleasant, “experience tells them they can no longer control the situation,” and subsequently, they do not try. They do not have the psychological stamina to improve the situation, even when it is technically possible.

In dialysis, learned helplessness can manifest pretty easily. Patients are forced into a painful (emotionally and physically) and unpleasant situation. No one wants or asks to be there. People with ESKD have ESKD for life, there isn’t a cure, there are treatment options. It’s not difficult to see how feelings of helplessness creep in when a person is passively tethered to a machine for hours on end without having much input or control over what is happening. This is the exact reason why we encourage patients to do things.

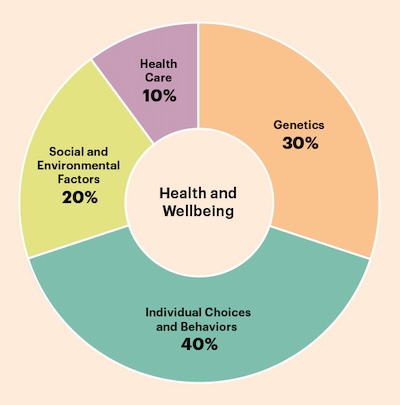

Here's a vital thing to know: the Kaiser Family Foundation estimates (see Figure. 1) that individual patient behavior drives 40% of health outcomes. This is as impactful as healthcare and genetics combined. We may not be able to cure a disease, fix genetics (yet), or save the whole of society from inequity… but we can empower patients to get the absolute most out of the 40% of control they do have. We need to harness that power to have successful patients. Teaching partners does not empower patients. Teaching partners sets up patients to be passive participants in their own lives, and

deprives them of their right to be self-sufficient. It is detrimental to their health outcomes.

Weaponized Incompetence

In other areas of partnership dynamics, there has been a lot of recent interest and discussion in unfair divisions of household labor and the burnout that comes with invisible, unpaid, and unrecognized work at home as a pervasive cause of resentment in domestic relationships. The term “weaponized incompetence” has emerged as a way of describing a passive-aggressive behavior pattern where a person pretends to be really bad at doing something s/he doesn’t want to do. This is done to manipulate someone else into taking over the task. Thus, the responsibility is basically kicked permanently elsewhere.

I can’t help but think about how much of what we are calling “learned helplessness” might actually be a form of weaponized incompetence, which is arguably a worse scenario, because it is grounded in manipulation, not in diminished capacity to act. As much as I’d like to delve into this more, I think it’s best if I just put the idea out there and let everyone digest it a little. For now, I’d rather get into how we can stop enabling both types of avoidance that lead to increased care partner burden.

What Can Nurses Do?

Home training nurses, at least in my experience, get a uniquely intimate view of partner dynamics. My intent is not to ostracize anyone—but if we are ever going to get to the bottom of how to prevent “care partner burnout” we should probably also look at what causes regular “partner burnout” and avoid encouraging codependency (helpless or weaponized) as a general rule. We certainly do not want to ever add fuel to those fires. A partnership is ideally a balanced, collaborative effort.

That is not fair, even in the presence of illness. Some partners do genuinely enjoy being actively involved, and that’s great—but the presence of supportive partners should never undermine the need to train the patient. When a patient uses a partner to avoid facing something unpleasant—or if a training program culture normalizes teaching a partner to take the brunt of the workload, the emotional needs of the partner are being deprioritized.

Here are some suggestions that I believe can really help change these patterns:

Use the PATH-D tools. These free downloadable resources were developed to help patients and care partners (when present) negotiate who will do which (if any) of the treatment-related tasks. There is a version for PD and one for home HD. At the very beginning of training, give your patient and any potential care partners a copy. Have each person fill it out alone, without input. Why? Because the PATH-D acts as a behavioral contract between the patient and the partner that explicitly defines the tasks at hand and determines what tasks each person is willing to take on. As you progress through training, administer the PATH-D again to see if any changes or re-delegations have been made. Go through the PATH-D at the end of training to make sure the partner and patient are (literally) on the same page. Discuss disagreements in responsibilities identified by the PATH-D before they turn into festering, resentful relationship issues. Over time, task management can and will change again. Each time a need for change is identified, use the PATH-D again.

Understand a want vs need for help. CMS does not define what a care partner is or “must” do. There is no minimum or maximum requirement—and certainly no rule that states a partner must perform all treatment tasks. So, let’s stop training that way. Work with patients to determine their maximum level of ability and use that as your expectation baseline. This is what we do in all other areas of medicine, and we need to do doing the same here if we want to call ourselves “patient-centered.” It is rare for an adult patient to truly be completely unable to participate.

Normalize solo patients. Even when they have willing care partners, life is strange, unpredictable, and random. “Man makes plans and God laughs,” you may have heard, and I don’t know how else to articulate this sentiment. Even under the best of circumstances, tomorrow is never a guarantee. When we create situations where a person is completely dependent on their partner for life sustaining treatment, there is potential to create an even bigger crisis should some accident or illness befall the partner. Care partners are fragile and mortal beings too. A care partner can fall and break a wrist, come down with COVID and need to hole up for a week, have a heart attack, run off with a neighbor, have a mental health breakdown, or even be hit by lightning. It’s all possible! The more a patient wants to and is able to do, the less likely it will be that treatment will be disrupted.

Let partners help in meaningful ways that do not cause burn-out. In addition to the PATH-D, patients and partners can collaborate on other tasks to ensure balance in the relationship. In my opinion, the best kind of care partner is one that knows how to help in an emergency, but in reality, only occasionally fetches things that are frustratingly out of reach for the patient. I call this the “Hey honey!” care partnership. As in, “Hey honey, I need new batteries for the TV remote and am stuck here for a while, can you bring them to me?”

Understand that unhealthy relationship dynamics that existed before an illness do not go away because of an illness. Sometimes, they even get worse. If you see red flags in a relationship, know that you can’t fix everything, nor is it your responsibility to try. You can take active steps to not make it worse, and therapy is always a fantastic suggestion.

Learn to recognize weaponized incompetence and learned helplessness, and point out observations to the social worker. When you notice that a partner relationship has these characteristics, make an effort to separate the patient and the partner during training as much as you are able. It is truly in the best interest of patients to give them control and encourage their active participation to the best of their capabilities. For most, this means running the entire treatment.

A Short Family Story

My step dad passed away during the COVID pandemic, but before that fiasco he was doing well on PD. He was, without a doubt, a man who enjoyed being doted on, and he did not enjoy having to do anything unpleasant. He considered everything “medical” to be unpleasant. My mother is a retired nurse. If it hadn’t been for my step-dad’s AMAZING PD training nurse (shout out to Linda!) he would have likely fallen into the exact learned helplessness trap described above, and my mom would have jumped in to save the day to her own detriment. That is how their “regular” relationship worked, so naturally, it would have extended further if promoted. But, they were trained for independence and self-reliance. My step-dad ultimately felt genuinely accomplished because he had control of his treatment. He would crack jokes when explaining dialysis that sounded like banter but was in good fun, “Yes, I do my dialysis at home, but my wife the nurse and my daughter the dialysis nurse do nothing! I do all of my treatment myself! They make me! Can you believe it?!”

Yes. Yes, we can believe it. In fact, this is the best way.

Comments